We all know grief now. We grieve the people we loved, but also the people we were before this pandemic began. If you’re old enough, you add it to the grief you’ve accrued over the years: for the children we were, the hopes we had, the people we longed to be. But if you’re lucky, the art that you need still finds you. It reminds you of who you are when you’ve forgotten, and gives you the power to imagine a life beyond this one. It lets you believe that what you’ve been robbed of will be found, that your home will come alive.

Tag: kids

-

Dan Sinker: The Magic of Pee-wee Herman in a Dark Year

-

Towards a True Children’s Cinema: on ‘My Neighbor Totoro’

This is an excellent essay on Miyazaki’s / Studio Ghibli’s place in the canon of art cinema, the nature of “boredom” in the life of children, and how cinematic experiences can be so much more for children than our U.S. blockbusters lead us to believe.

When Roger Ebert asked Miyazaki about the “gratuitous motion” in his films—the bits of realist texture, like sighs and gestures—Miyazaki told Ebert that he was invoking the Japanese concept of “ma.” Miyazaki clapped three times, and then said, “The time in between my clapping is ma.” This calls to mind the concept of temps morts, or dead time, in the European art cinema of the 1960s. Temps morts is a pause, a beat, a breath, a moment that doesn’t advance the plot. But far from being dead, Miyazaki’s moments of “ma” are full of life—there is a simple joy in watching his worlds move. In “animating”—breathing life into—a world that looks like our own, Miyazaki carries forward a spirit from the very beginning of film history.

This is one of the greatest descriptions of the power of animation that I’ve read in a long time, and something that you can see in all of the small moments of Miyazaki’s films.

On children and boredom:

But I think some of the common thinking about children’s boredom and attention is inaccurate. Children are bored standing in line at the bank or the post office, certainly—they have no banking of their own to do, no mail of their own to send. But if you were to put a child and an adult in an empty room full of scattered objects, I suspect the adult would grow bored much faster. […] A child can never exhaust the possibilities of a park or a neighborhood or a forest. Totoro is travel and transit and exploration, set against lush, evocative landscapes that seem to extend far beyond the frame.

Bonus: this essay is from an full Studio Ghibli issue of Bright Wall / Dark Room! I need to start reading this magazine.

-

littleBits: the Pipe Cleaner and Popsicle Stick of the 21st Century

littleBits — pre-assembled circuit modules that are designed to help kids, novices, and anyone curious about programming, logic, and electronics get started without the obstacles of soldering or wiring. The various modules snap together with small magnets, a great idea to keep it as simple as playing with LEGOs.

At littleBits, we believe we need to create scientific thinkers and problem-solvers, and interventions need to occur early. The time is ripe to create the pipe cleaner and the popsicle stick of the 21st century.

(Via Make)

-

Ad Rock Sneaks in “Cookie Puss” on Nickelodeon

[Alas, video has been removed from YouTube]

DJ Jazzy Jay and Afrika Bambaataa on a 1984 episode of Nickelodeon’s Live Wire, showing kids how to scratch. Awesome enough as it is, but WAIT A MINUTE — is that a 17-year-old Ad-Rock in the audience sneaking in a plug for Cookie Puss at 4:18??!

(Via Dangerous Minds and They Might Be Giants)

-

James Gurney Draws Dinosaurs All Day

One time my son had a friend over. I heard the friend say in a stage whisper, “Does your dad have a job?” No, my son replied. “He just stays home and draws dinosaurs all day.” James Gurney, creator and illustrator of Dinotopia, on growing up with art. (His Gurney Journey blog on illustration, drawing, and painting is very much worth reading, by the way)

-

Softening the edges

The first such Disney film I ever saw was Snow White, which added considerably to my experience of wonderful fear and terror, even though its heroine was a doll. This, I have been told, was because it was made by German refugees who had a sense of the darkness of the old stories. The film Bambi diminished the sense of real forests and creatures I had found in the book. The unbearable thing was the filming of the Jungle Books. Disney cartoons use the proportions of human baby faces – those wide eyes, those chubby cheeks we respond to automatically. The black hunting panther, the terrible strong snake, the wolf pack and its howl, the cringing tiger became dolls and toys like Pooh, Piglet and Eeyore, and some crucial imaginative space was irretrievably lost.

From AS Byatt’s essay in the Guardian about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland / Through the Looking-glass, which offers some great insight into the difference between Lewis Carroll’s imagined spaces and narrative and those of other popular (later, 20th Century) fantasy stories for children.

-

Guns That Look Like Toys

Baltimore Police Department: Guns That Look Like Toys. Not a lot of info on this one, and the police report is from a couple of years ago, but have the criminals finally figured out that the law requiring toy guns to be clearly painted in comical neon colors can work both ways? How come these all seem to have been painted by the same gun shop in Wisconsin?

On the flip side this reminds me of the Entertech uzi motorized water gun I had as a kid (check out this commercial – almost unthinkable now, but I remember having a lot of fun with it at the time). These were pretty much the last realistically-painted gun toys sold in large stores in America after legislation passed in many states in 1988 following multiple incidents of children being mistakenly shot and killed by the police. That cultural shift led into the Super Soaker generation, which is actually a pretty fascinating story in and of itself.

(Via Schneier on Security, who reports that there a posters warning about painted guns in the NYC subways currently)

-

The Textbook Myth

The Texas Tribune posted a great article last week following up on the Texas SBoE brouhaha, outlining why ideologically-fueled edits to textbooks rarely have much effect on the actual curricula taught in schools and why Texas no longer “wags the textbook industry tail”. The concluding paragraph is a bit depressing, though:

But that’s the thing: Most history textbooks are not written by historians — self-respecting or otherwise. Foner’s book, a cohesive narrative researched and written by one scholar, is the exception. Most elementary and secondary texts are written by committees of a dozen or more writers, hired hands who don’t own their work and can’t object to any changes multiple publishing house editors make to appease whichever politicians or bureaucrats control the millions being spent. They are cooked quickly and to order, pressed together from hundreds of standards that reflect, in many ways, the lowest common denominator of thousands of opinions. They are, in short, the chicken nuggets of the literary world.

Can we get Jamie Oliver to tackle this educational malnourishment, too?

-

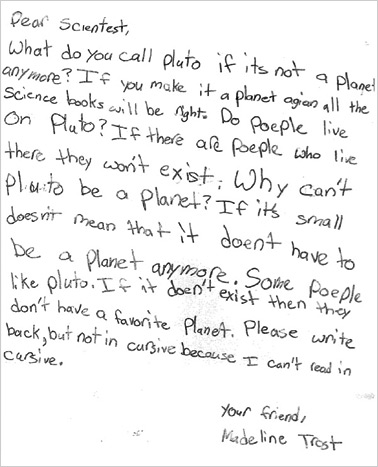

Neil Degrasse Tyson Gets Hate Mail from Kids About

Neil Degrasse Tyson gets hate mail from kids about Pluto. The shift in tone from letter to letter is great, as kids begin to accept that “thats science”.

(Via Coudal Partners)

-

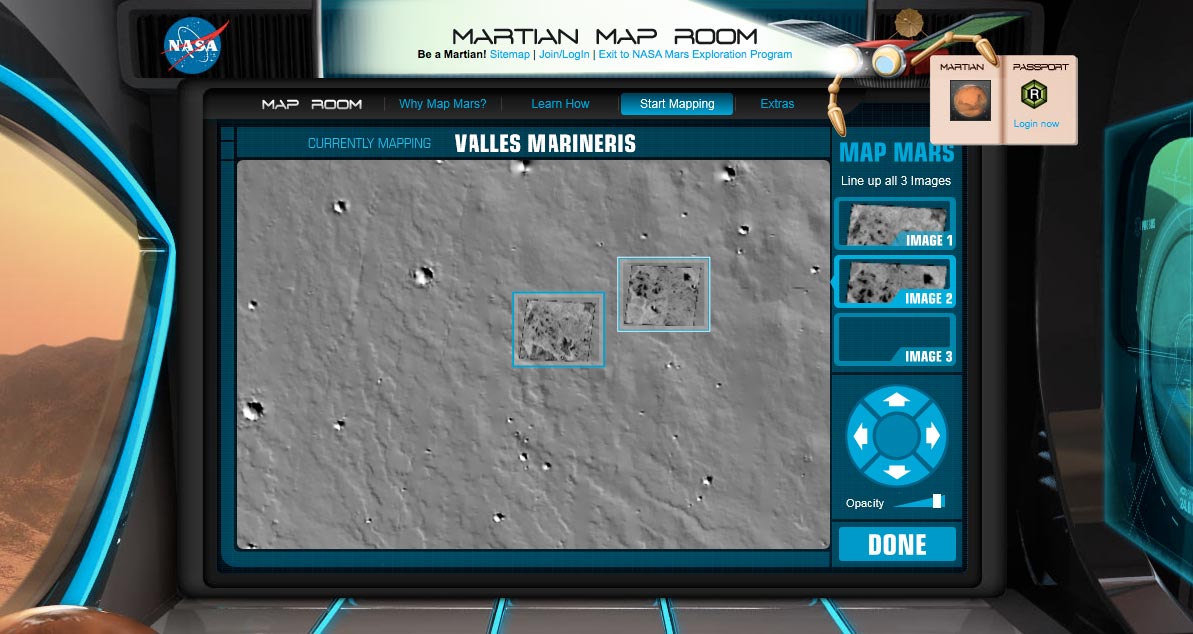

NASA’s Be a Martian

NASA has launched (pardon the sorta pun) a new website for kids called Be a Martian, with various games that allow them to rack up points and earn badges as they learn about the red planet. The interesting twist? The games are actually crowdsourced work, real data sorting through the aligning of map images taken by Mars Odyssey explorer with elevation images from the Mars Global Surveyor project. Kids play a game, NASA gets useful data that’s otherwise hard to get computationally. The Register has a good writeup of the project.