Links and write-ups about beautiful things from around the web!

-

Making of Pharcyde Drop

The behind-the-scenes of one of my favorite Spike Jonze music videos, Pharcyde’s Drop (original video). The group had to learn to rap backwards to create the right lipsync for the effect, so Jonze hired a professional linguist to help transcribe the reversed audio track!

-

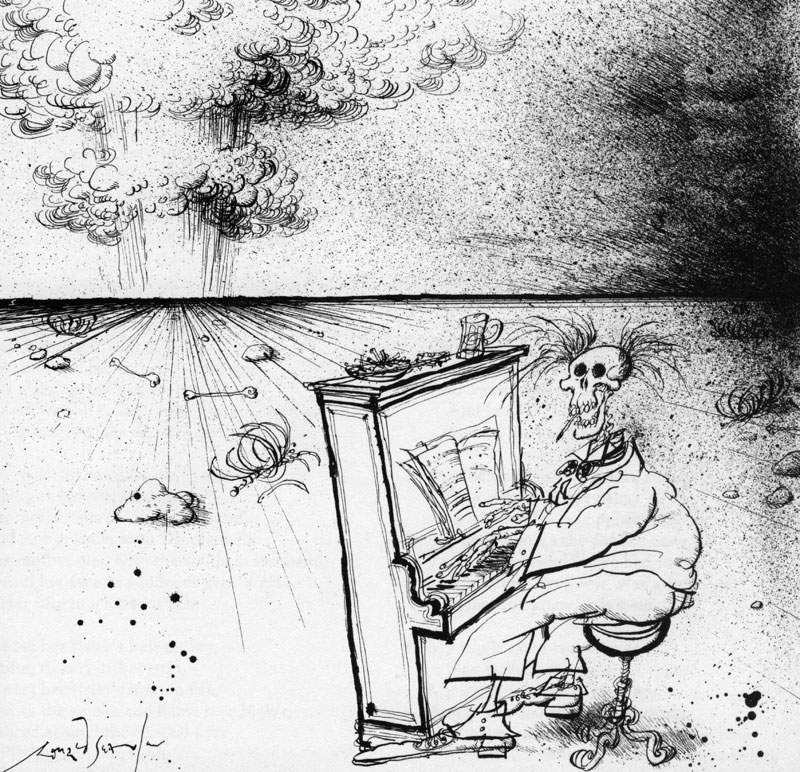

Tom Lehrer Ronald Searle

Awesome thing that I didn’t realize I had on my bookshelf: the Tom Lehrer sheet music songbook I’ve had since I was a kid was illustrated by cartoonist Ronald Searle. I must have been unfamiliar with Searle the last time I looked through this book — his scratchy style complements Lehrer’s acerbic wit nicely.

The whole book, “Too Many Songs By Tom Lehrer with not enough drawings by Ronald Searle”, is available for perusal on Scribd, in case you’re the sort that enjoys songs about masochism, the periodic table, bull fighting, nuclear annihilation, and Ivy League snobbery…

-

The Very Heart of Noise

I frequently hear music in the very heart of the noise… George Gershwin on Rhapsody in Blue’s inspiration, the rhythm of the city train.

-

Genius Childhood Recaptured at Will

But genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recaptured at will.

Charles Baudelaire, from The Painter of Modern Life. I often see this quoted by itself, so here’s some context:

But genius is no more than childhood recaptured at will, childhood equipped now with man’s physical means to express itself, and with the analytical mind that enables it to bring order into the sum of experience, involuntarily amassed. To this deep and joyful curiosity must be attributed that stare, animal-like in its ecstasy, which all children have when confronted with something new, whatever it may be, face or landscape, light, gilding, colours, watered silk, enchantment of beauty, enhanced by the arts of dress. A friend of mine was telling me one day how, as a small boy, he used to be present when his father was dressing, and how he had always been filled with astonishment, mixed with delight, as he looked at the arm muscle, the colour tones of the skin tinged with rose and yellow, and the bluish network of the veins. The picture of the external world was already beginning to fill him with respect, and to take possession of his brain. Already the shape of things obsessed and possessed him. A precocious fate was showing the tip of its nose. His damnation was settled.

-

Bute Tarentella

[Video no longer available]

Experimental animation pioneer Mary Ellen Bute’s short film Tarentella was selected this week for preservation in the National Film Registry as a culturally significant film. From the press release:

“Tarantella” is a five-minute color, avant-garde short film created by Mary Ellen Bute, a pioneer of visual music and electronic art in experimental cinema. With piano accompaniment by Edwin Gershefsky, “Tarantella” features rich reds and blues that Bute uses to signify a lighter mood, while her syncopated spirals, shards, lines and squiggles dance exuberantly to Gershefsky’s modern beat. Bute produced more than a dozen short films between the 1930s and the 1950s and once described herself as a “designer of kinetic abstractions” who sought to “bring to the eyes a combination of visual forms unfolding with the … rhythmic cadences of music.” Bute’s work influenced many other filmmakers working with abstract animation during the ‘30s and ‘40s, and with experimental electronic imagery in the ‘50s.

Bute’s final piece was an interpretation of Finnegans Wake, one of the very few attempts ever made at staging Joyce’s novel of troubled dreams.

-

Caterpillars whistle for safety

From the Journal of Experimental Biology comes news that caterpillars are able to force air through their bodies to ‘whistle’ as a defense mechanism when they’re spotted by predators. These aren’t exotic bugs, either: they can be found all over the U.S., even here in Austin, Texas (guess I’d better listen carefully next time I’m in the backyard). From the Nature abstract:

When under attack, walnut sphinx caterpillars (Amorpha juglandis), whistle. An 1868 Canadian Entomologist paper, “Musical larvae,” first reported these shrieks, but their purpose wasn’t clear.

Jayne Yack at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, and her team now show that the whistle, produced through openings along the body called spiracles, is a defence against predators. Simulated attacks with blunt tweezers caused the caterpillars to pull their heads back, forcing air through two of the spiracles in a succession of squeaks.

There’s a video of the little guy whistling available in .mov format. I think I’d squeak too if someone was jabbing at me with a pair of forceps…

-

The Unsuccessful Self-Treatment of a Case of Writer’s Block

Via NCBI ROFL, a single-page paper submitted to the 1974 volume of the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, “The Unsuccessful Self-Treatment of a Case of ‘Writer’s Block’”.

This amazing research was verified and extended upon in 2007: “A Multisite Cross-Cultural Replication of Upper’s (1974) Unsuccessful Self-Treatment of Writer’s Block”

-

Cryovolcano on Titan

Volcanoes spewing ice and slush instead of lava on Titan! From NASA: Cassini Spots Potential Ice Volcano on Saturn Moon

Scientists have been debating for years whether ice volcanoes, also called cryovolcanoes, exist on ice-rich moons, and if they do, what their characteristics are. The working definition assumes some kind of subterranean geological activity warms the cold environment enough to melt part of the satellite’s interior and sends slushy ice or other materials through an opening in the surface.

I suddenly have a hankering to play Metroid…

-

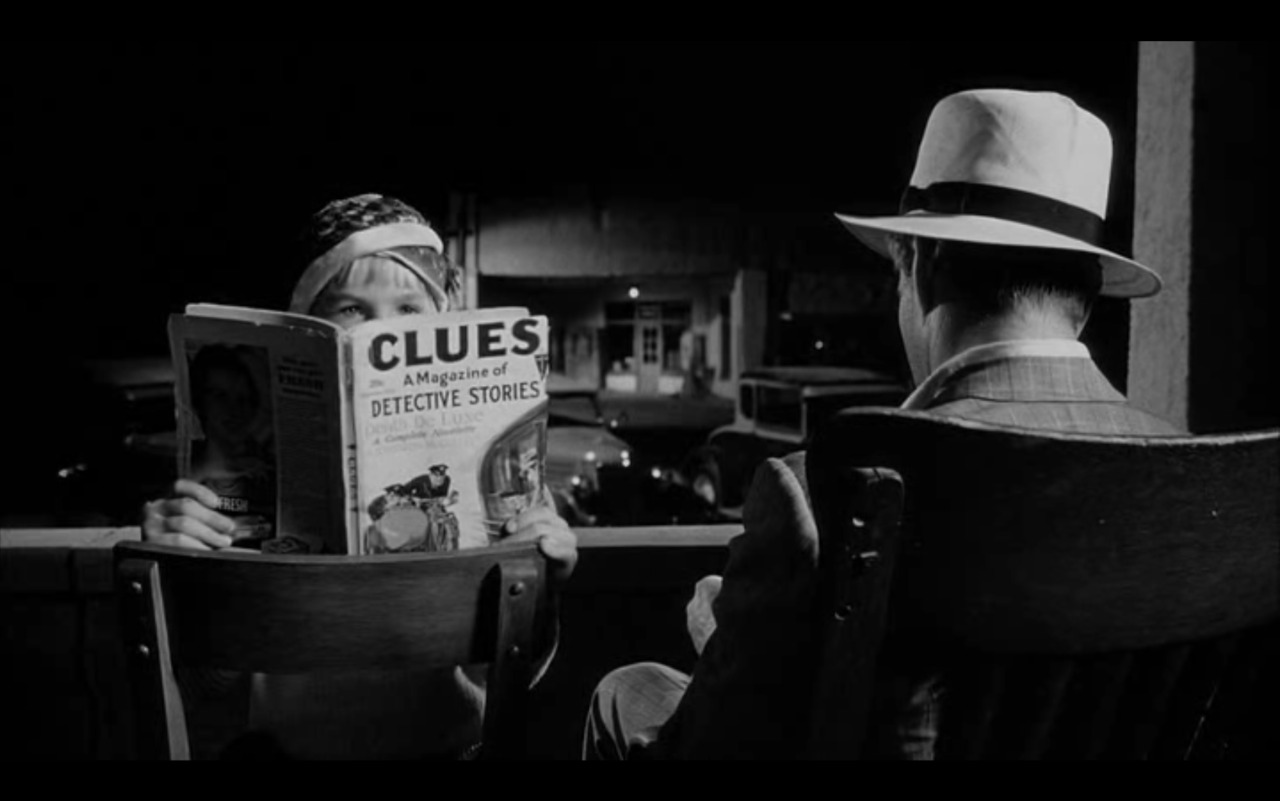

Paper Moon

Peter Bogdanovich’s Paper Moon, an enjoyably bleak con artist road movie comedy set in the Great Depression. I’ll agree with Roger Ebert’s assessment that 9-year-old Tatum O’Neal “somehow resembles Huckleberry Finn more than any little boy I can imagine.”