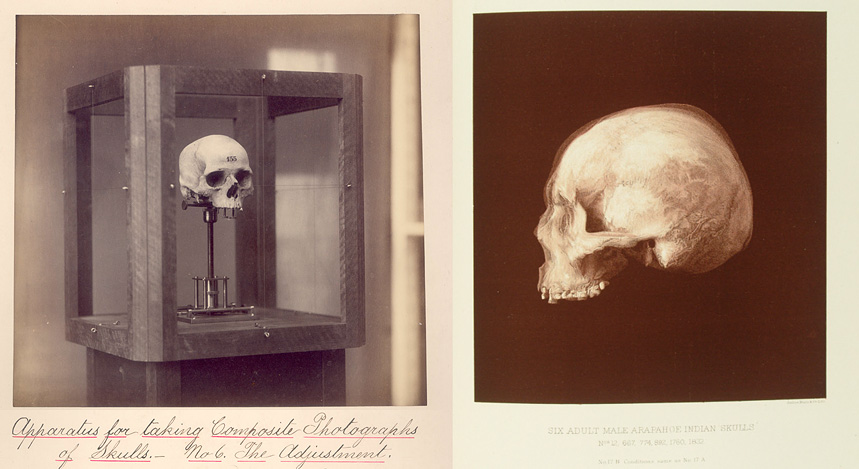

Ghostly photos from the Otis Archives depicting a novel circa-1885 piece of scientific analysis equipment: Apparatus for taking Composite Photographs of Skulls. Basically a wood and brass frame with a craniophore in the middle, the tool made it possible to position and align multiple skulls so composite photos could be taken accurately from the front, side, and rear views. The image on the right, for example, is a composite of five or six (or more?) separate skulls. From a contemporary anthropology journal describing the process:

Then the anterior frame and the lateral frame next to the window are lowered ; a black velvet background is hung on the posterior frame ; a large white cardboard is hung on the frame further from the window ; the brass-work is occluded with small velvet screens, and the picture is taken.

The photographs record composites of skulls from various Native American and Cook Island tribes (as seen in the archives of the Clark Institute), so I first thought that the measurements were sadly being undertaken for the sake of scientific racism, the darker side of physical anthropology, which was still in vogue in the 1880s.

That may be the case, but thankfully the full story is somewhat more complex: the inventor of the apparatus, Washington Matthews, an army surgeon-ethnographer-linguist, wrote extensively on the Siouan languages while stationed in the Dakotas, reportedly married and had a son with a woman from the Hidatsa tribe, was initiated into some aspects of the Navajo tribe, and also contributed substantially to the understanding and recording of the Navajo culture, which previously had been considered primitive by the Europeans:

Dr Matthews referred to Dr Leatherman’s account of the Navahoes as the one long accepted as authoritative. In it that writer has declared that they have no traditions nor poetry, and that their songs “were but a succession of grunts.” Dr. Matthews discovered that they had a multitude of legends, so numerous that he never hoped to collect them all: an elaborate religion, with symbolism and allegory, which might vie with that of the Greeks; numerous and formulated prayers and songs, not only multitudinous, but relating to all subjects, and composed for every circumstance of life. The songs are as full of poetic images and figures of speech as occur in English, and are handed down from father to son, from generation to generation.