From the New York Times review of Mike Mignola’s new comics collection Bowling with Corpses & Other Strange Tales from Lands Unknown, this paragraph celebrating the relationship between text, illustration, and fantasy mapmaking resonated with me:

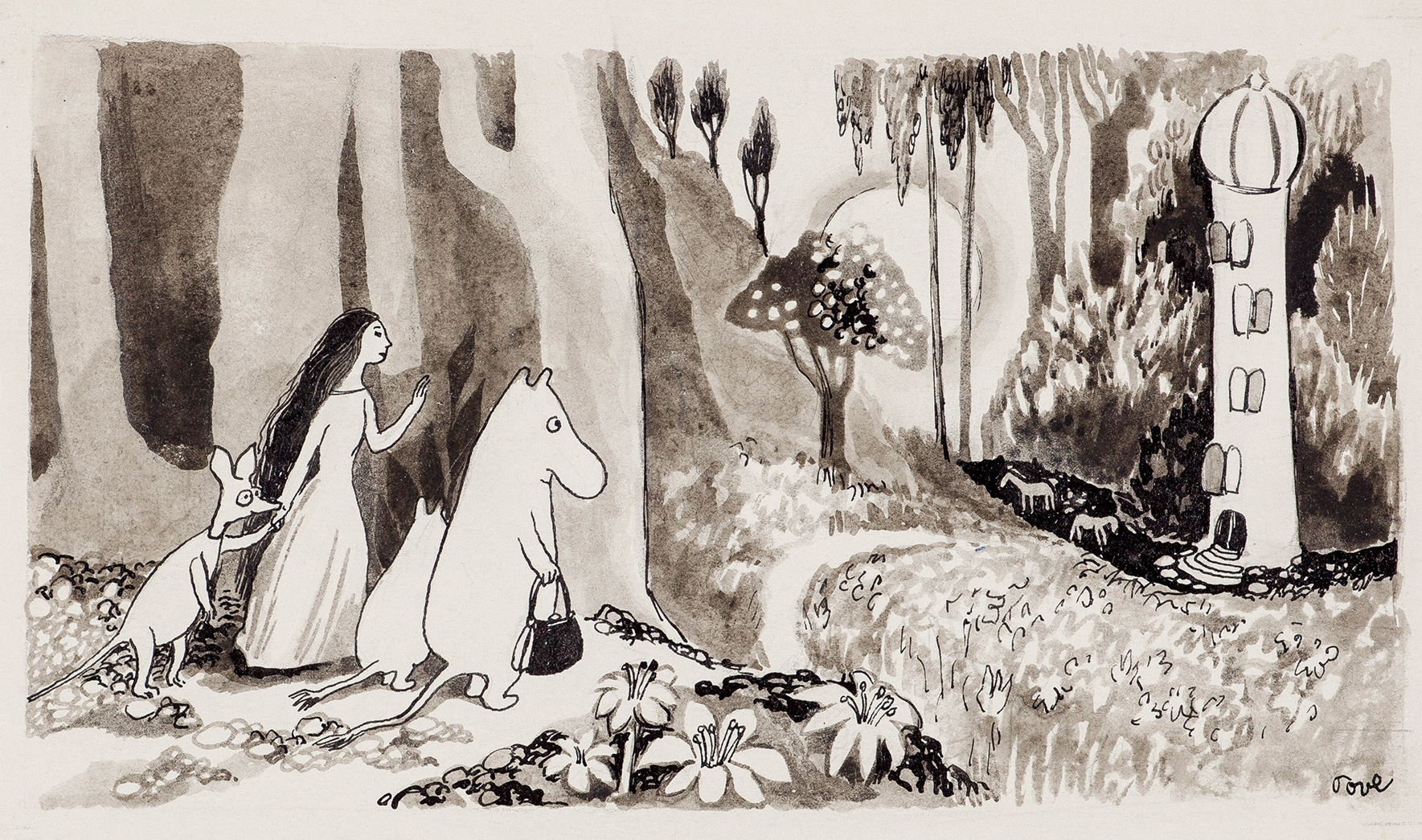

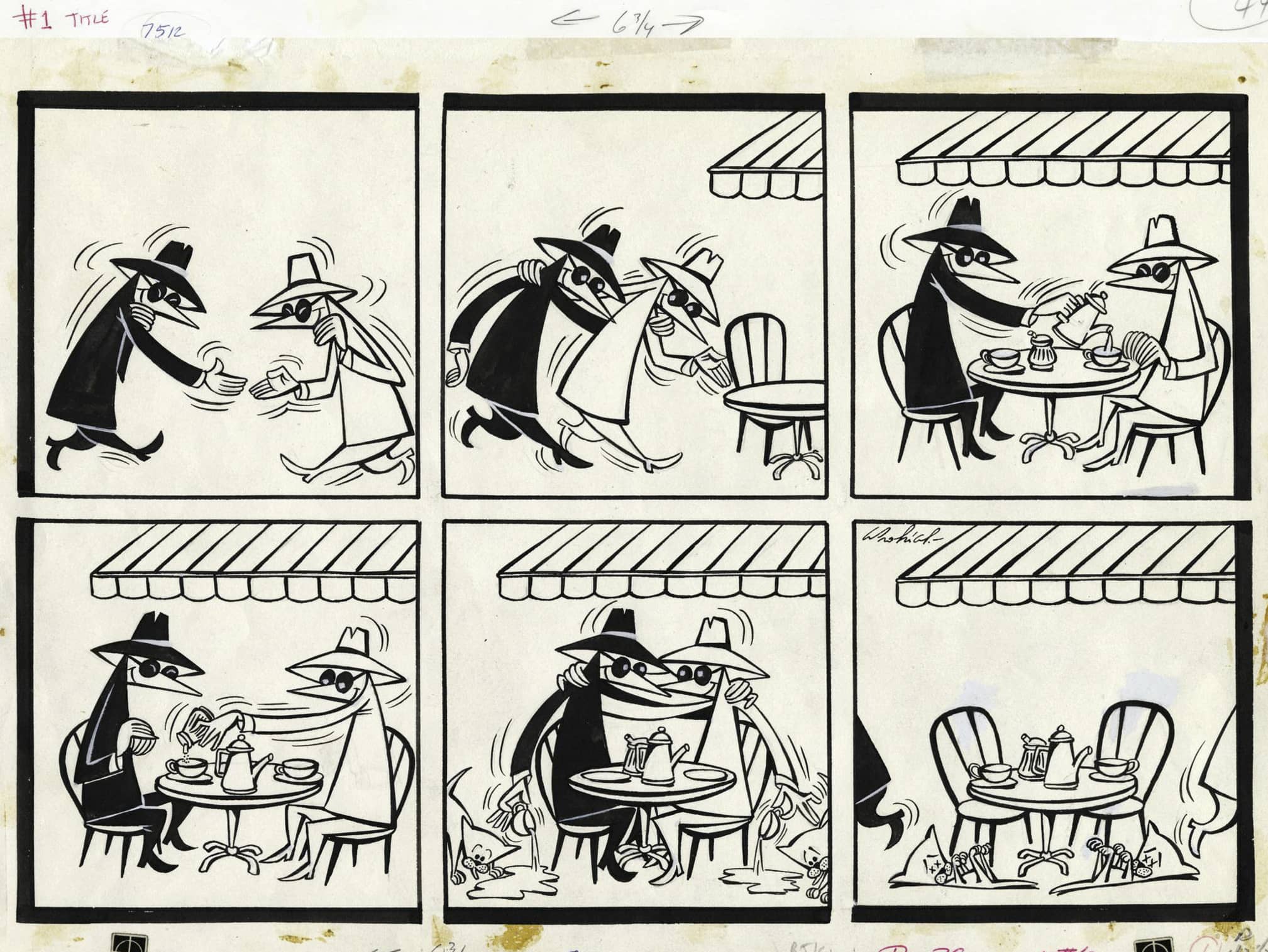

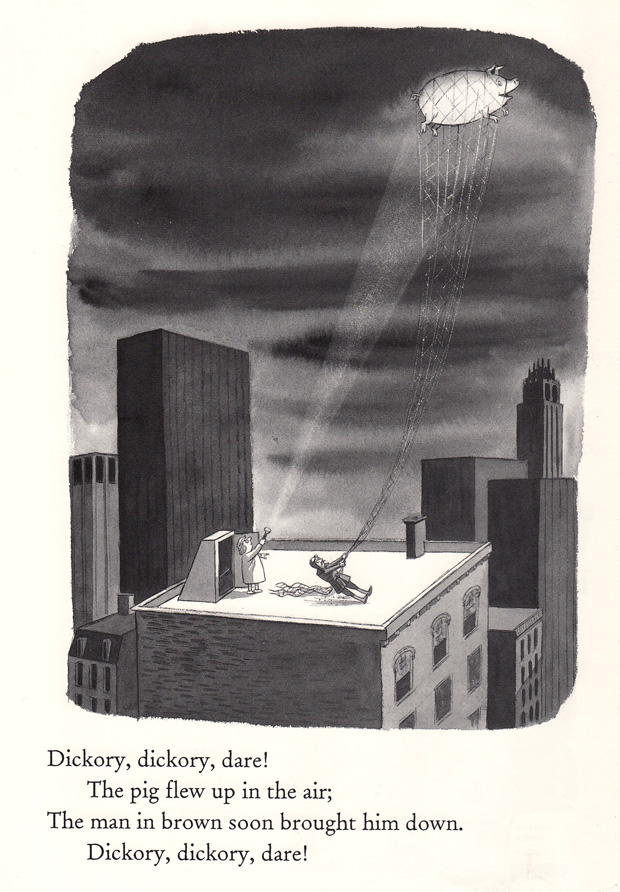

The book is a good reminder that the history of imaginative literature is also the history of illustrated literature, and not just for children. Gustave Doré is as useful a guide to Milton’s “Paradise Lost” as he is to Charles Perrault’s fairy tales; Botticelli’s drawings and maps of hell give depth and gravity to the “Inferno” as reliably as Virgil gives directions to Dante. Every lover of high fantasy keeps one finger on the flyleaf where the map is printed.

See also: the NY Times “overlooked” obituary for Karen Wynn Fonstad, whose maps of Middle-Earth and the D&D worlds of Dragonlance (Krynn) and Forgotten Realms were some of my most thumbed-through books of my early teenage years. Until this article I hadn’t really thought about the depth to which her geographical form of illustration felt as substantive as the worldbuilding of the original source material she was drawing from.