Links and write-ups about beautiful things from around the web!

-

Korg M01

Nobuyoshi Sano (composer on the arcade series Ridge Racer and Tekken) and Yasunori Mitsuda (who worked on Secret of Mana and composed the music for Chrono Trigger, along with a number of other Square games) have started a new studio called Detune to continue their work on bringing synthesizer emulators to the Nintendo DS. Here Sano demos their upcoming KORG M01 release, which replicates the late 1980’s sounds of the KORG M1.

(Via GameSetWatch)

-

Yukikaze

-

Thingamagoop Pianola

https://vimeo.com/4342116

A Bleep Labs Thingamagoop played like a player piano (in a very basic sense). Would be cool to see a longer strip with an actual melody!

(Via Make)

-

Moulage

WAX MODEL from 1917: Smallpox lesions on face of 15 year old boy

Sorry for the icky photo, folks, just wanted to share a striking bit of anatomical illustration! This image led me down the rabbit hole of looking into the art of moulage, casting realistic wax models with “wounds” and other dermatological problems for use in medical training. Obviously a much better way of introducing a classroom full of doctors to diseases than wheeling in an actual smallpox patient. There’s a photo book on the subject called Diseases in Wax: The History of Medical Moulage that I might have to track down. At $180 on Amazon, though, I sure hope that the library here has it…

(Via the Otis Historical Archives of the National Museum of Health & Medicine on Flickr)

-

Radiolab: Strangers in the Mirror

Another excellent short episode of Radiolab, featuring a conversation with two people I wouldn’t expect to hear on stage together:

Oliver Sacks, the famous neuroscientist and author, can’t recognize faces. Neither can Chuck Close, the great artist known for his enormous paintings of … that’s right, faces.

Oliver and Chuck–both born with the condition known as Face Blindness–have spent their lives decoding who is saying hello to them. You can sit down with either man, talk to him for an hour, and if he sees you again just fifteen minutes later, he will have no idea who you are. (Unless you have a very squeaky voice or happen to be wearing the same odd purple hat.)

If you’re interested in the science of face perception, I stumbled across this relevant paper this week: Cortical Specialization for Face Perception in Humans (pdf) co-authored by Tel Aviv University’s Galit Yovel.

-

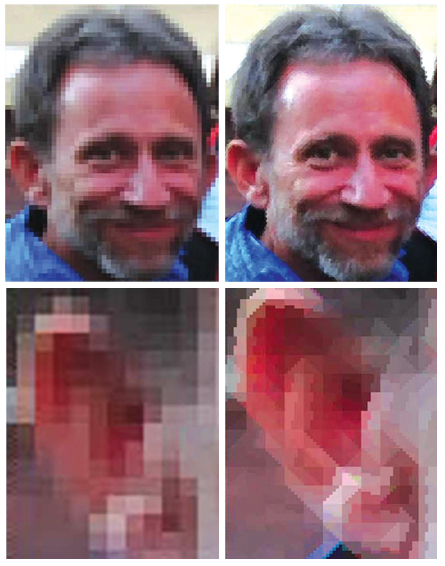

Non Square Pixels

The man who created the first scanned digital photograph in 1957, Russel Kirsch, pioneer of the pixel, apologizes in the May/July issue of Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Now 81 years old, he offers up a replacement (sorta) for the square pixel he first devised: tessellated 6×6 pixel masks that offer much smoother images with lower overall resolution. The resulting file sizes are slightly larger but the improved visual quality is pretty stunning, as seen in the closeup above. His research was inspired by the ancient 6th Century tile mosaics in Ravenna, Italy.

There are a lot of comments out there complaining that square pixels are more efficient, image and wavelet compression is old news, etc., and that’s true, but if you actually read the article you’ll find that the point isn’t so much the shape, the efficiency, or even the capture/display technology needed, but rather that this could be a good method for reducing the resolution of images somewhat while still retaining visual clarity, important in medical applications and in situations where low-resolution images are still tossed around.

Bonus: the man in the demo photo above is his son, the subject of the first-ever digital photograph!

(Via ScienceNews)

-

Dark pulse quantum dot diode laser

A paper in Optics Express describing a quantum dot-powered “dark pulse” laser. I was totally hoping that this was a device that could emit some kind of anti-light to darken the room, but what they’re really talking about is a laser that can go from light to dark very fast. The on/off pulses are down in the 90-picosecond range, useful for even more precise timekeeping or for new innovations in networking / telecom.

(Via The Register)

-

Matisse Photos

Art and Science Collide in Revealing Matisse Exhibit from Northwestern News on Vimeo.

Computational image processing researchers at Northwestern University teamed up with art historians from the Art Institute of Chicago to investigate the colors originally laid down by Matisse while he was working on Bathers by a River:

Researchers at Northwestern University used information about Matisse’s prior works, as well as color information from test samples of the work itself, to help colorize a 1913 black-and-white photo of the work in progress. Matisse began work on Bathers in 1909 and unveiled the painting in 1917.

In this way, they learned what the work looked like midway through its completion. “Matisse tamped down earlier layers of pinks, greens, and blues into a somber palette of mottled grays punctuated with some pinks and greens,” says Sotirios A. Tsaftaris, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at Northwestern. That insight helps support research that Matisse began the work as an upbeat pastoral piece but changed it to reflect the graver national mood brought on by World War I.

The Art Institute has up a nice mini-site about Bathers and the accompanying research, including some great overlays on top of the old photos to show the various states the painting went through during the years of its creation.

(Via ACM TechNews)

-

Artoolkit in Quartz Composer

Augmented Reality without programming in 5 minutes

I can vouch that this works, and it’s pretty straightforward once you manage to grab and build the two or three additional Quartz Composer plugins successfully. I had to fold in a newer version of the ARToolkit libs, and I swapped out the pattern bitmap used to recognize the AR target to match one I already had on hand – the default sample1 and sample2 patterns weren’t working for me for some reason. Apart from that, Quartz Composer’s a lot of fun to use, almost like building eyecandy demos with patch cables and effects pedals, and it’s already on your system if you have Xcode.

(Via Make)

-

Maya Blue

Ancient pigment history is fascinating. From dried beetles (carmine) to sea snails (Tyrian purple) to ground up human and feline mummies (the rather uncreatively-named Mummy brown), colors come from some weird places. I’d heard of Maya Blue before, but didn’t realize that it’s more of a process rather than a specific mineral pigment. The color was made by intercalating indigo (añil) into fine clay over continuous heat. The slow fusing with clay made the paint exceptionally resistant to weather and acidic conditions (and even modern solvents), and the process wasn’t fully understood / rediscovered until a few years ago. Cooking it up may have been ritualistic, as the incense copal was often burned in the same bowls. The color was important in sacrifice rituals as well: when the Sacred Cenote of Chichen Itza was dredged back in 1904, a a layer of blue silt 14-feet-thick was found at the bottom (sensationalism aside, the silt was likely more from all of the blue-painted pots tossed in than the blue-painted people…I hope).

From Discoblog:

The researchers knew that the Mayans made their blue by heating the pigment with palygorskite (a type of clay); their analysis showed that this heating allowed the pigment to enter tiny channels in the clay which are sealed after the mixture cools, protecting and keeping the pigment true blue for centuries.