Gathering data is not a neutral act, it will alter the power balance, usually in favor of the people collecting the information.

From What the Sumerians can teach us about data, a blog post noting that the predecessor of writing was the depiction of data, a concept that helped establish the hierarchical systems of power in the early city-states. (I like his comparison between the data-protecting curses inscribed on the cuneiform tablets and the FBI WARNING notices on VHS!)

Tag: history

-

What Sumerians Can Teach Us About Data

-

Bell Labs Hamlet from 1885

Seen above is a green disc, wax on brass, with an early recording of Hamlet’s “To be or not to be…” soliloquy, that likely hasn’t been heard in over 125 years. Created by Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Laboratory in the late 19th Century and sent to the Smithsonian for archiving as they were created, the paranoid Bell failed to provide a playback mechanism for these discs, for fear that his competitors would appropriate his innovations.

Researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories are working on recovering these early audio recordings with a system called IRENE/3D that creates 3D optical scans of the old record-like discs:

Using methods derived from our work on instrumentation for particle physics we have investigated the problem of audio reconstruction from mechanical recordings. The idea was to acquire digital maps of the surface of the media, without contact, and then apply image analysis methods to recover the audio data and reduce noise.

The nifty thing about this form of hands-off scanning is that it can accommodate many types of otherwise mechanically incompatible media, from discs made of metal or glass to wax cylinders (quick, someone set this up to scan the Lazarus bowl!!). The 18-second snippet of Hamlet audio from the green disc above (maybe the voice of Bell himself?) has been posted on YouTube, or you can download more examples from the project in WAV and MP3 format.

(Via PhysOrg)

-

Marconi, Hacked in 1903

Want to expose a rival’s poor security implementation? What better way than to demonstrate the weakness in public, in front of a gathered crowd? From a New Scientist story of very early 20th-Century hacktivism:

LATE one June afternoon in 1903 a hush fell across an expectant audience in the Royal Institution’s celebrated lecture theatre in London. Before the crowd, the physicist John Ambrose Fleming was adjusting arcane apparatus as he prepared to demonstrate an emerging technological wonder: a long-range wireless communication system developed by his boss, the Italian radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi. The aim was to showcase publicly for the first time that Morse code messages could be sent wirelessly over long distances. Around 300 miles away, Marconi was preparing to send a signal to London from a clifftop station in Poldhu, Cornwall, UK.

Yet before the demonstration could begin, the apparatus in the lecture theatre began to tap out a message. … Mentally decoding the missive, Blok [Fleming’s assistant] realised it was spelling one facetious word, over and over: “Rats”. A glance at the output of the nearby Morse printer confirmed this. The incoming Morse then got more personal, mocking Marconi: “There was a young fellow of Italy, who diddled the public quite prettily,” it trilled.

The radio-hacker was Nevil Maskelyne, a magician and rival inventor who was interested in developing wireless technology but who had been frustrated by the broad patents granted to Marconi. Bonus trivia: Nevil’s father was John Nevil Maskelyne, magician and inventor of the pay toilet, and his son was Jasper Maskelyne, a magician and inventor (see a family connection here?) who allegedly helped develop some of the famous optical diversions and camouflage trickery for the British military during WWII (his inflatable tanks remind me of the Potemkin Army thing I posted a couple of years back…)

-

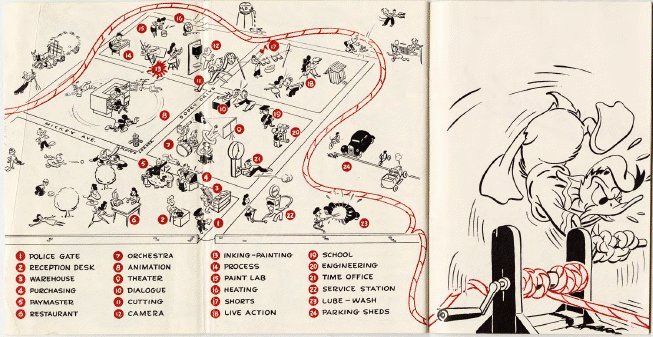

Disney Employee Handbook 1943

Studio map from a nifty Disney employee handbook circa 1943. The info in the booklet is mostly uninteresting, but it’s peppered with wartime secrecy, unions (represented by a headless, walking union suit — weird!) , and the gender biases that were prevalent at Disney at the time (sorry, ink-and-paint girls, the “penthouse club” is for men only!). This book was produced not long after the famous animator’s strike of 1941, which was unpleasantly lampooned through the clowns in Dumbo, and would have been read during a time of high tension between the studio and the employees.

(Via @dajanx)

-

STRIPPED: the Comics Documentary

Do you enjoy newspaper comics? Want to learn more about their history and place in the world through interviews with a laundry list of comic artists? Then you might be interested in helping these guys in Kickstarter finish out their documentary: STRIPPED: The Comics Documentary

(Via The Comics Curmudgeon)

-

On gunpowder, ice cream, and sound symbolism

From the post Language of Food: Ice Cream, a fascinating article linking the history of gunpowder, ice cream, linguistics, and even a bit of marketing insight:

Something similarly beautiful was created as saltpeter and snow, sherbet and salt, were passed along and extended from the Chinese to the Arabs to the Mughals to the Neapolitans, to create the sweet lusciousness of ice cream. And it’s a nice thought that saltpeter, applied originally to war, became the key hundreds of years later to inventing something that makes us all smile on a hot summer day.

If you like food, language, or science, the full post is worth a read.

(Via Language Log)

-

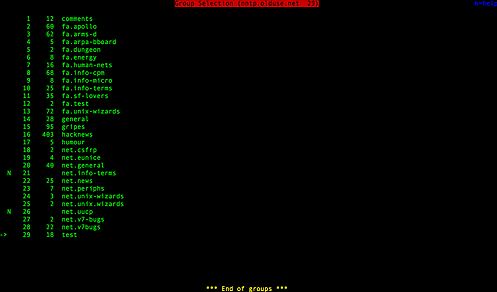

olduse.net Brings Back Usenet from 30 Years Ago

Screenshot from an interesting project, olduse.net ― Usenet posts reappearing in realtime as they did exactly 30 years ago, a new way of experiencing the history of the early Net. See how things were mere months before the launch of B-News, long before the Great Renaming and the creation of the alt.* hierarchy, and best of all, the introduction of spam is more than a decade away still!

You can use either the browser-based client to poke through the messages, or point your favorite NNTP client to the site and experience it as you would the real Usenet. Nice!

Also, I like this answer from the FAQ:

Can I post to olduse.net?

Your posts will be accepted, but will not show up for at least 30 years. 🙂(Via Waxy Links)

-

IBM 2250 Graphics Display

The IBM 2250 graphics display, introduced in 1964. 1024×1024 squares of vector-based line art beamed at you at 40Hz, with a handy light pen cursor. Much more handy than those older displays that just exposed a sheet of photographic film for later processing!

(Via Columbia University, via Ars Technica’s recent quick primer on computer display history)

-

Bute Tarentella

[Video no longer available]

Experimental animation pioneer Mary Ellen Bute’s short film Tarentella was selected this week for preservation in the National Film Registry as a culturally significant film. From the press release:

“Tarantella” is a five-minute color, avant-garde short film created by Mary Ellen Bute, a pioneer of visual music and electronic art in experimental cinema. With piano accompaniment by Edwin Gershefsky, “Tarantella” features rich reds and blues that Bute uses to signify a lighter mood, while her syncopated spirals, shards, lines and squiggles dance exuberantly to Gershefsky’s modern beat. Bute produced more than a dozen short films between the 1930s and the 1950s and once described herself as a “designer of kinetic abstractions” who sought to “bring to the eyes a combination of visual forms unfolding with the … rhythmic cadences of music.” Bute’s work influenced many other filmmakers working with abstract animation during the ‘30s and ‘40s, and with experimental electronic imagery in the ‘50s.

Bute’s final piece was an interpretation of Finnegans Wake, one of the very few attempts ever made at staging Joyce’s novel of troubled dreams.

-

Ancient astronomy: Mechanical inspiration

New research on the Antikythera mechanism hints that we might be looking at its use and meaning from the wrong perspective. From Nature:

Now, however, scientists delving into the astronomical theories encoded in this quintessentially Greek device have concluded that they are not Greek at all, but Babylonian — an empire predating this era by centuries. This finding is forcing historians to rethink a crucial period in the development of astronomy. It may well be that geared devices such as the Antikythera mechanism did not model the Greeks’ geometric view of the cosmos after all. They inspired it.