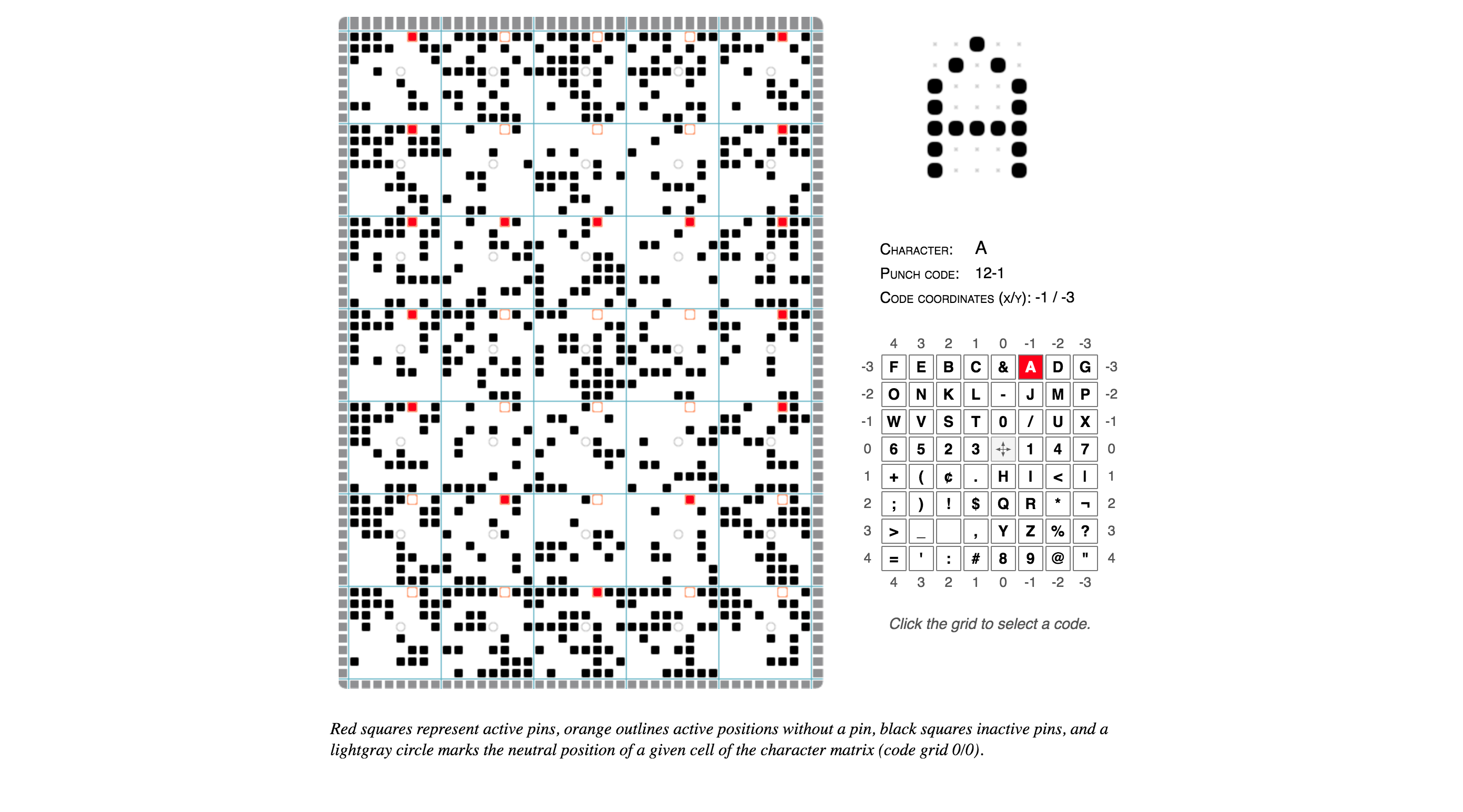

This interactive visualization of the history of the Latin alphabet from a team at the Urban Complexity Lab at the University of Applied Sciences Potsdam (wow, they have some other really interesting looking work on their Projects page!) is like catnip to typography fans. It traces a family tree from early Roman monumental writing up to modern slab serifs — a good reminder that this alphabet design has been pretty constant (aside from the additional development of uncials and lowercase scripts in the 800s) for the better part of 2500 years.

Our main concern was to show the diversity and variance of the Latin alphabet over the centuries. It is often suggested that the Roman Capitalis evolved to Antiqua scripts to today’s Grotesk in a linear way. However, we believe that this is only one possible view among many. Like any cultural development, the history of type and script is, at its core, a network. Over the centuries, designers have learned from others, referred to existing designs, and developed variants. There were times of greater standardization and then again times of great variance. The Arete project wants to show and clarify this diversity and these different design lines.

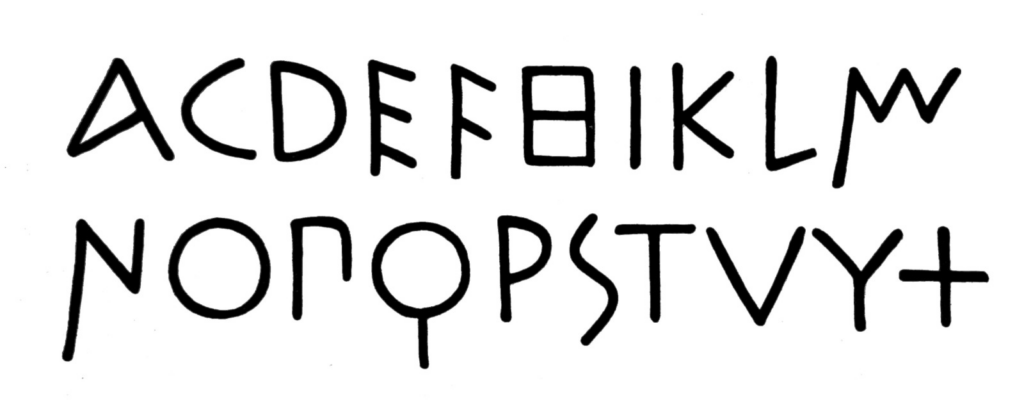

Also I like that the above earliest example they have looks like it could almost be an “Adam Norwood” wordmark if I just took out a few extraneous letters…