From a good piece in this month’s Vanity Fair, “Coloring the Kingdom”, about the often-unsung Ink and Paint “girls” that cranked out most of the hand painting for Disney’s early feature days:

The end of the assembly line usually inherits all the problems. Preparing the animators’ vision for camera required the inking and painting of thousands of fragile, combustible cels with perfect refinement. During Snow White, it was not at all unusual to see the “girls”—as Walt paternalistically referred to them—thin and exhausted, collapsed on the lawn, in the ladies’ lounge, or even under their desks. “I’ll be so thankful when Snow White is finished and I can live like a human once again,” Rae wrote after she recorded 85 hours in a week. “We would work like little slaves and everybody would go to sleep wherever they were,” said inker Jeanne Lee Keil, one of two left-handers in the department who had to learn everything backward. “I saw the moon rise, sun rise, moon rise, sun rise.” Painter Grace Godino, who would go on to become Rita Hayworth’s studio double, also remembered the long days merging into nights: “When I’d take my clothes off, I’d be in the closet, and I couldn’t figure it out: am I going to sleep or am I getting up?”

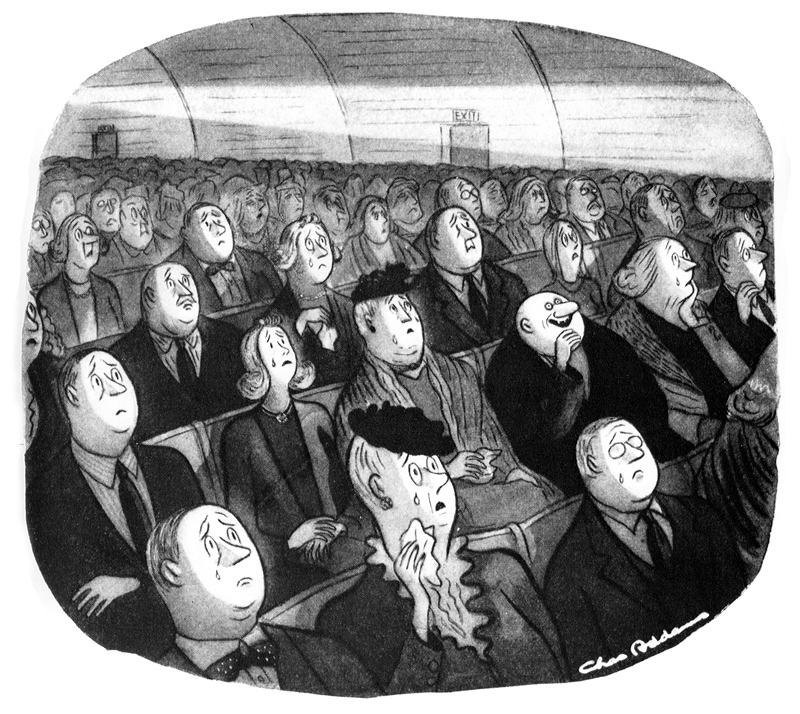

(Via Mayerson on Animation. Photo © Walt Disney Productions/Photofest.)