Links and write-ups about beautiful things from around the web!

-

C’est l’heure d’or

Designers love noodling about perfecting the design of chairs. Linguists seem to love discussing why “cellar door” is cited as the most beautiful phrase in English. From Language Log’s The Romantic Side of Familiar Words:

And in fact the specific meaning of cellar door isn’t quite as irrelevant as people imagine. The undeniable charm of the story — the source of the delight and enchantment that C. S. Lewis reported when he saw cellar door rendered as Selladore –– lies the sudden falling away of the repressions imposed by orthography (which is to say, civilization) to reveal what Dickens called “the romantic side of familiar things." It’s the benign cousin of the disquietude we may feel when familiar things are suddenly charged with strange and troubling feelings, which Freud analyzed in his essay on the Unheimlich or uncanny. As Freud observed, heimlich can mean either “homey, familiar,” or “"concealed, withheld, kept from sight.” He goes on: “‘Unheimlich’ is customarily used, we are told, as the contrary only of the first signification of’ heimlich’, and not of the second. …” But he notes that the second meaning is always present as well: “everything is unheimlich that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light.” Something is unheimlich, he says, because it “fulfils the condition of touching those residues of animistic mental activity within us and bringing them to expression.“

The unheimlich object, that is, is a kind of portal to the romance and passion that lie just beneath the surface of the everyday. In the world of fantasy, that role is suggested literally in the form of a rabbit hole, a wardrobe, a brick wall at platform 9¾. Cellar door is the same kind of thing, the expression people keep falling on to illustrate how civilization and literacy put the primitive sensory experience of language at a remove from conscious experience – "under a spell, so the wrong ones can’t find it” — until it’s suddenly thrown open. It would be hard make that point using rag mop.

-

Bill Plympton’s New BBQ Short

Bill Plympton’s got a new short aimed at the younger set on the way, about a cow who wants to become a hamburger. No dialog or sound effects; simple, blocky colors inspired (“ripped off”, in his words) by Kandinsky; and final line art rendered with Sharpie. Looks good to me!

If you’re up in NYC for the premiere (which will be at an Austin-themed BBQ joint in Manhattan that takes its inspiration from Kreuz Martket!), you can hit him up for a free cow drawing.

-

Animation: production vs. post

Mark Mayerson writes a pretty good rebuttal to the idea that the animators that worked on James Cameron’s Avatar were shortchanged by the film’s placement as a live-action feature:

“I’ve written extensively on how fragmented the process of making an animated film is and how so many of the acting decisions are made before the animator starts work. The character designs, the storyboard and the voice performance all make acting decisions that constrain the animator’s interpretation. There is no question that motion capture is yet another constraint, probably larger than all the others. To insist that Avatar is an animated film is to marginalize animators even more than they are in what are generally considered animated films. Is this the direction we want things to go? Better to agree with James Cameron and focus our attention on films where animators create, not enhance, performances.”

-

“I don’t carry a sketchbook to do pretty drawings in it.”

Storyboard artist and animation historian Mark Kennedy on keeping a sketchbook:

I’ve seen artists on the Internet question the necessity for this, saying that you can’t really learn anything about drawing by carrying a sketchbook, and that the drawings you do in a sketchbook are always dashed off, careless and sloppy. […]

The real reason I carry a sketchbook is so that I can record and remember details that I observe. Drawing from real life is the best way to teach yourself how people look, act and move in a naturalistic way (and help you remember it later). Life drawing and studying the work of other artists and animators are great learning experiences, but those things aren’t the same as studying real life. A great life drawing is an amazing feat and you can learn a lot about drawing and anatomy by going to life drawing. But very few life drawings give you a lot of information about the model’s personality and what kind of human being they are. You’re never going to create an original story or character based on a life drawing model you saw.

-

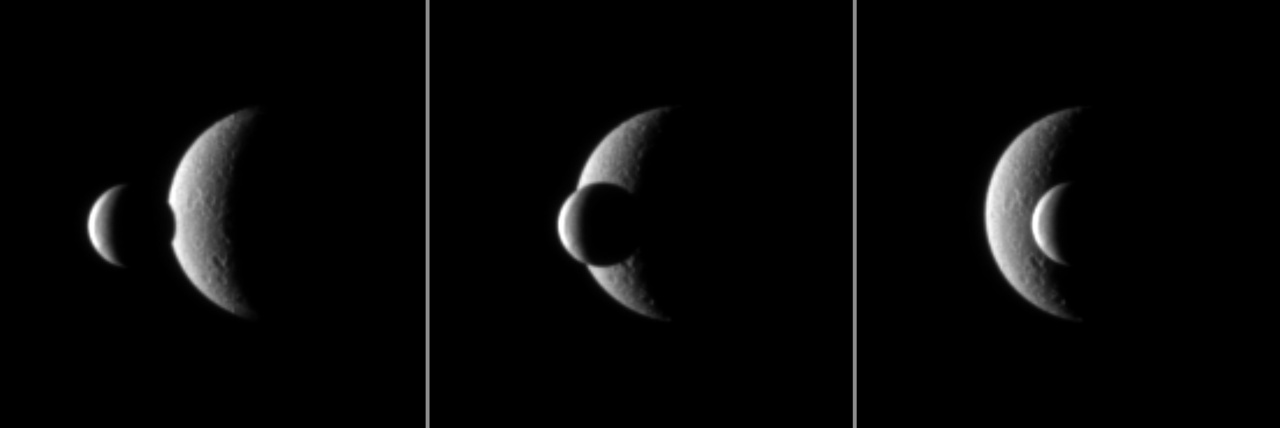

Saturn’s Moon Enceladus Transiting in Front of Rhea

Saturn’s moon Enceladus transiting in front of its larger moon Rhea, as seen from a couple million miles away by the Cassini spacecraft, in photographs that span about one minute’s worth of time. That we can know to point cameras at this kind of event and get images this nice is a bit of a wonder to me.

(Via Discover)

-

The Virtue of Vagueness

From Nature’s review (sorry about the academic paywall) of the new book Not Exactly: In Praise of Vagueness:

Although scientists strive for increasing clarity in their measurements and concepts, it is often uncertainty that spurs new thinking. The haziness of the species notion set the young Charles Darwin pondering evolution. Francis Crick observed that if he and James Watson had worried about how to define the gene in the 1950s, progress in molecular biology would have stalled. “In research the front line is almost always in a fog,” Crick wrote in his autobiography. Even today there is no consensus definition of the gene.

Another excerpt:

“Sometimes,” confesses the computer scientist Kees van Deemter, “one just has to be sloppy.”

-

Vanity Fair on Disney’s Ink & Paint “Girls”

From a good piece in this month’s Vanity Fair, “Coloring the Kingdom”, about the often-unsung Ink and Paint “girls” that cranked out most of the hand painting for Disney’s early feature days:

The end of the assembly line usually inherits all the problems. Preparing the animators’ vision for camera required the inking and painting of thousands of fragile, combustible cels with perfect refinement. During Snow White, it was not at all unusual to see the “girls”—as Walt paternalistically referred to them—thin and exhausted, collapsed on the lawn, in the ladies’ lounge, or even under their desks. “I’ll be so thankful when Snow White is finished and I can live like a human once again,” Rae wrote after she recorded 85 hours in a week. “We would work like little slaves and everybody would go to sleep wherever they were,” said inker Jeanne Lee Keil, one of two left-handers in the department who had to learn everything backward. “I saw the moon rise, sun rise, moon rise, sun rise.” Painter Grace Godino, who would go on to become Rita Hayworth’s studio double, also remembered the long days merging into nights: “When I’d take my clothes off, I’d be in the closet, and I couldn’t figure it out: am I going to sleep or am I getting up?”

(Via Mayerson on Animation. Photo © Walt Disney Productions/Photofest.)

-

A Telephonic Conversation

Without answering, I handed the telephone to the applicant, and sat down. Then followed that queerest of all the queer things in this world,—a conversation with only one end to it. You hear questions asked; you don’t hear the answer. You hear invitations given; you hear no thanks in return. You have listening pauses of dead silence, followed by apparently irrelevant and unjustifiable exclamations of glad surprise, or sorrow, or dismay. You can’t make head or tail of the talk, because you never hear anything that the person at the other end of the wire says.

Mark Twain, writing an article for the June, 1880 issue of The Atlantic on the oddity of telephone conversations. Still relevant in our age of disjointed retweets, wall posts, and other overheard messages.

(Via Discover)

-

Mia Doi Todds Open Your Heart Directed by Michel

Mia Doi Todd’s Open Your Heart directed by Michel Gondry, the master of making absolutely joyous videos using sublimely simple ideas.

(Via Coudal)

-

Nanothermal Trumpets

Converting heat energy directly into sound using tiny electrical conductors is a 100-year-old idea for an alternative to the mechanical voice coil wire + moving diaphragm design of traditional speakers, but new research recently submitted to Applied Physics Letters demonstrates a new, actually feasible approach to making these speakers-on-a-chip. Still way too quiet and underpowered for use as a loudspeaker, but might have some novel applications in the near future as research progresses.

I like the name given to the 100 year old invention, though: the thermophone.