Like the hero of “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,” also based on one of his books, the creatures of Dahl’s valley seem to know more than they’re letting on; perhaps even secrets we don’t much want to know. Children, especially, will find things they don’t understand, and things that scare them. Excellent. A good story for children should suggest a hidden dimension, and that dimension of course is the lifetime still ahead of them. Six is a little early for a movie to suggest to kids that the case is closed. Oh, what if the kids start crying about words they don’t know? – Mommy, Mommy! What’s creme brulee?“ Show them, for goodness sake. They’ll thank you for it. Take my word on this.– From Roger Ebert’s review of Fantastic Mr. Fox

(Via the Ghibli Blog)

Tag: movies

-

Like the Hero of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate

-

The Virgin Spring: Like Leaves in a Storm

“You see how the smoke trembles up in the roof holes? As if whimpering and afraid? Yet it’s only going out into the open air, where it has the whole sky to tumble about in. But it doesn’t know that. So it cowers and trembles under the sooty ridge of the roof. People are the same way. They worry and tremble like leaves in a storm because of what they know, and what they don’t know.” — from Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring

-

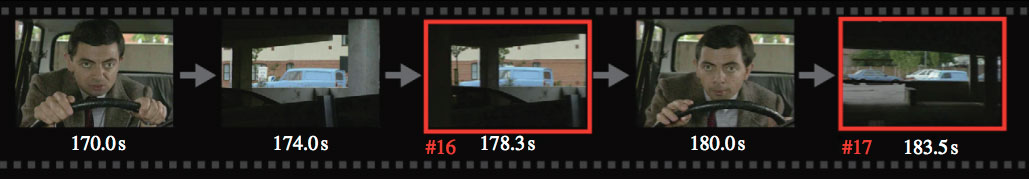

The Timing of Blinks

Update 11/3/2009: RadioLab did a short piece in October on this phenomenon, even discussing the Mr. Bean test with the Japanese researchers: http://blogs.wnyc.org/radiolab/2009/10/05/blink/

———-

From recent research out of Japan: “The results suggest that humans share a mechanism for controlling the timing of blinks that searches for an implicit timing that is appropriate to minimize the chance of losing critical information while viewing a stream of visual events.” In simpler words, the researchers found that audiences watching movies with action sequences have a strong tendency to synchronize their blinking so that they don’t miss anything good.

I’m not sure that this is interesting in and of itself, but it’s, um, eye-opening to think that we have our eyes closed for nearly 10% of our waking life. That’s roughly 10 full minutes of every movie lost to blinking. I imagine that editors already take this phenomenon into account, at least to some extent?

Full text available available in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B – Biological Sciences. Thanks, Creative Commons!

(Via NewScientist)

-

From pathos to bathos

The Three Stooges attempted pathos in Cash and Carry (1937). The Stooges arrive at their home, a dilapidated shack in the city dump, only to find a little boy they don’t know doing his homework at the kitchen table. The Stooges do not react with great sentiment to this child. Larry pipes up, “Come on, beat it.” But, then, they realize that the boy is wearing a leg brace and needs the support of a crutch to stand and walk. The boy tells the Stooges that his mom and dad are gone and he’s being raised by his big sister. Moe, normally gruff and scowling, smiles sympathetically and softens his voice. He has never acted more tenderly to another individual. But the other two Stooges do not show much concern. […] Seconds after meeting the crippled orphan boy, Curly accidentally hits Moe in the head with a pipe and it’s back to their usual comedy business. A pathos comedy was, in the end, no more significant to the Stooges than a haunted house comedy.

From Why You Want to Bring Me Down?, a great comparison of the use (and perhaps more often, misuse) of pathos in comedies, from Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd to Adam Sandler and Robin Williams.