Solaris (1972). Something of a lyrical Russian follow-up to 2001: A Space Odyssey, a story of personal grief and longing set aboard a space station hovering over an abyssal alien ocean. Great use of understated sets and on-Earth scenery with allusions to the style of the Old Masters. Between Solaris, Alphaville, and Children of Men, I’m discovering that my favorite cinematic dystopian futures are the ones that make little or no effort to appear futuristic.

Tag: cinema

-

Solaris

-

Hirokazu Kore-edas ワンダフルライフ Wandâfuru Raifu (Afterlife)

From Hirokazu Kore-eda’s ワンダフルライフ (Wandâfuru raifu), released in the U.S. in 1998 as Afterlife. This is likely my favorite movie of all time. Dig up a copy at your neighborhood indie video store when you get a chance, it’s good. It’s a simple, quiet parable about life, death, loss, memory, love, and cinema, somewhere between Kurosawa’s Ikiru and Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine.

After whining for years about someone borrowing my out-of-print DVD copy without returning it, I finally looked around and discovered the vastly superior Japanese NTSC Region 2 copy of the movie. ¥3,990 later, I’m now able to enjoy it again as I saw it at the theater in anamorphic widescreen, optional subtitles, and none of the horrible digital low-pass smoothing that someone thought would “fix” the grainy 16mm film’s appearance. Time for a movie screening, I think…

-

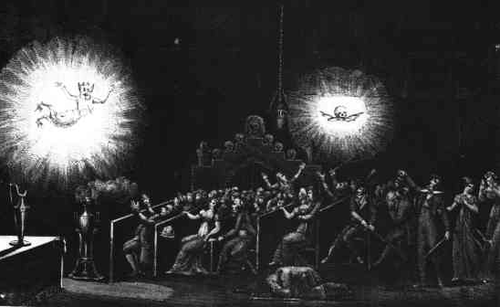

Phantasmagoria

It’s interesting to look back at the hype and spectacle of the early CD-ROM games (with novelties like Myst flying off the shelf the medium was hailed as the savior of declining video game sales) as a parallel to the hype and spectacle of the real 18th Century phantasmagoria and magic lantern parlor theater. From classic gaming site GOG.com’s short editorial piece commemorating their recent addition of Roberta William’s popular 1995 FMV horror game Phantasmagoria:

In the mid-1700s, long before horror pioneers like Alfred Hitchcock, films such as Dracula and Frankenstein, and even cinema itself, the predecessor to horror cinema was born in a tiny coffee shop in Leipzig, Germany. The proprietor of the shop, Johann Schropfer, welcomed patrons with a warm beverage and an invitation to shoot the breeze and some stick in his adjoining billiards room. But the extra attraction of running a table after a long workday didn’t do much to boost Schropfer’s steadily declining patronage. In an effort to drum up business, Schropfer cast out pool tables and converted the billiards parlor into a séance chamber. […]

By the late 1760s, Schropfer’s once-deserted shop had evolved into a hotspot where patrons gasped in awe at ghostly images projected onto smoke, chilling music, ambient sounds, and burning incenses whose aromas were evocative of malevolent forces. The masterful performance put on by Schropfer proved so lucrative that the coffee-shop-owner-turned-showman took his show on the road throughout Europe until 1774, at which time Schropfer, perhaps haunted by the specters he alleged to call forth from the afterlife, took his own life.

-

Hito Steyerl: In Defense of the Poor Image

The poor image is a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.

[…]

At present, there are at least twenty torrents of Chris Marker’s film essays available online. If you want a retrospective, you can have it. But the economy of poor images is about more than just downloads: you can keep the files, watch them again, even reedit or improve them if you think it necessary. And the results circulate. Blurred AVI files of half-forgotten masterpieces are exchanged on semi-secret P2P platforms. Clandestine cell-phone videos smuggled out of museums are broadcast on YouTube. DVDs of artists’ viewing copies are bartered.3 Many works of avant-garde, essayistic, and non-commercial cinema have been resurrected as poor images. Whether they like it or not.

– Excerpted from Hito Steyerl’s piece in e-flux journal #10

(Via Rhizome)

-

Johan Grimonprez’s Double Take

A short clip from Double Take, a film by media artist Johan Grimonprez (there are a handful of other clips on YouTube). “They say that if you meet your double, you should kill him.” Hitchcock versus Hitchcock versus the Cold War, with cinematic history folding in on itself. There’s a worthwhile interview with Grimonprez over on the Cinema Scope website with more info.

-

The Shuftan process

An early film special effect using a partly-silvered mirror to reflect and superimpose miniatures or other off-camera devices.

-

Cinéorama

The original IMAX experience, circa 1900.

-

In 1903 the Specialty Watch Company Helios Built

In 1903, the specialty watch company Helios built a trial run of miniature Boilerplates. The master of the hoax, an expert on Victorian automata, Paul Guinan, “tried” to “rebuild” one of these. The head resembles gas masks that soldiers wore in World War I, but as ornamental brass. The chest is as tubular as a Franklin stove, but gleaming with Baroque detail. Its knobby limbs were fully articulated , like an armature for special effect stop-motion seventy years later, or a thing in The City of Lost Children. […] For over a century, thousands of boilerplates have come down to us. They wait patiently. Patience has always been a virtue of the boilerplate; and of all hoaxes, including the Wizard of Oz himself. Norman M. Klein, in Building the Unexpected. From The Vatican to Vegas, 2004 p179.

-

Potemkin Villages Were a New Mode of Special

Potemkin villages were a new mode of special effects as power, as the erasure of memory in the late eighteenth century. But the principle evolves beyond one’s wildest imagination. All movie sets are Potemkin villages before they are shot as film. And all wars since 1989 have become Potemkin villages when they appear on global media. And yet, Baroque special effects already pointed toward this problem by 1650, that Baroque illusion served uneasy alliances to cover up the decay and misery of the kingdom. Norman M. Klein, in Scripted Spaces and the Illusion of Power, 1550-1780. From The Vatican to Vegas, 2004 p131

-

Comenius Begins His Story with a Pilgrim Who Is

Comenius begins his story with a pilgrim who is given mystic spectacles. But the lenses are cursed, ground by Illusion, rims hammered by Custom. Optical gimmicks were pervasive in many churches and theaters by 1622. Perspective could be accelerated or decelerated by tilting floors, narrowing walls, adding a deep focal point. Special effects were featured on ceilings: trompe l’oeil, accelerated perspective, anamorphosis – to induce a moment of wonder – a “vertigo” when the lid of a building simply dissolved. To many, these phantasms were progress, practical advances. But to Comenius, they might be the serpent’s eye.

Indeed in Labyrinth of the World, the spectacles distort God’s nature. To quote Shakespeare, the are “almost the natural man … [but] Dishonour traffics with man’s nature.” They are a prosthesis upon the eye, as McLuhan would say. To Comenius, they are an evil, not a cheerful global village. They make true distances vanish; ugly turns beautiful; black becomes white. However, luckily for Comenius’s pilgrim, these demonic spectacles do not fit properly. He can sneak looks below the rim, see the human labyrinth as it really is. If this were film, I would call what the pilgrim finds beneath his spectaceds Baroque noir, the town with no soul.

Norman M. Klein, in Scripted Spaces and the Illusion of Power, 1550-1780. From The Vatican to Vegas, 2004 p112. Describing a story from Comenius’s The Labyrinth of the World.